Neocon writer Bret Stephens debuted his New York Times columnist byline with an argument against “certainty” and the “human wreckage of scientific errors married to political power” in the ongoing U.S. climate change conversation. He explicitly did not deny climate change or global warming, but rather he urged against “[c]laiming total certainty about the science, [thereby traducing] the spirit of science and [creating] openings for doubt whenever a climate claim proves wrong.” It was overly heady-sounding at times and a rather shoddily written column, but the reaction — and the reaction to the reaction to the reaction to the… — revealed something vital enough to the climate change conversation that it almost justifies the New York Times‘ hire.

Listen: Stephens’ career is riddled with utter bullshit. But there’s something very important at play here, in the wake of his column. I don’t think “total certainty” was the right wording, but indeed there is something that the progressive left does to contort the “spirit of science,” and it’s not relegated merely to climate. Scientific data becomes an end in itself for many, rather than the conduit for meaningful exchange. It becomes a clever sign at a march. A hashtag. One more thing to get bent out of shape about, and nothing more.

The social media outrage against the piece was immediate, and thousands reported via Twitter from the front lines of the NYT subscriptions cancellation hotline. (Read this thread for a pristine example of what I’m getting at.) Other columnists and pundits pounced on the narrative, eviscerating the Times for publishing this thing. (Here‘s the Washington Post‘s Erik Wemple, to whom I’ll return shortly.) It became the swirling vortex of hot takes du jour, and the tempest has yet to settle.

I’ll assume that, for many, that’s the point. It’s something to feed on. And truly, yes, the column itself is structured horrendously and unhelpfully. The Hillary Clinton conflation lede is weak and transparent in its right-wing source material, and Stephens is not helping himself by burying his argument two-thirds of the way into the piece. Stephens did, however, link back to Andy Revkin’s far more interesting 2016 piece on his own paradigm shifts in thinking about climate change. No one seems to be talking about that, perhaps only because Revkin is less a firebrand than Stephens — less of a catchy subject for a tweetstorm.

Last year, Revkin confronted his own storied career and the angular twists it had taken. His reporting had taken him deep into the world of climate and energy policy, labyrinthine places where solutions, sometimes arcane, are being hammered out at all times like metal. But the pace isn’t keeping up with the pace of global warming. It’s Sisyphean, and Revkin realized that telling “the ultimate environmental story—our evolving and worrisome relationship with Earth’s atmosphere and climate”— was going to require a broader and almost eschatological understanding of humanity’s grasp and reach. The scientific data wasn’t the end — wasn’t the headline, the hashtag — but rather it was the stepping stone to a far more important conversation about climate, one that will probably be challenging or difficult.

That sort of thing doesn’t sit well with most environmentalists.

Later in his career, Revkin began exploring what I would call a more holistic approach to climate debate. It is possible to say with 100-percent all-in certainty that the climate is changing (has changed) fundamentally because of humans’ relationship with it and to say that maybe that certainty isn’t serving the purpose we think it is, that a bit of reasoned debate among people with different ideas about all of that is kind of healthy for us. Perhaps we should push established facts to the side and begin work on the next set of recognitions: like what we need to do to save the planet. Here’s Revkin:

Journalism’s norms also required considering the full range of views on a complex issue like climate change, where science only delineated the risk but societal responses would always be a function of considering various tradeoffs. In 2007, I included Bjorn Lomborg’s climate book, Cool It, in a roundup of voices from “the pragmatic center.”

Lomborg, a Danish political scientist, became a widely quoted contrarian pundit after the publication of The Skeptical Environmentalist, a previous book that had challenged—and was vigorously challenged by—the environmental science community.

Given how Lomborg hadn’t resisted having his arguments wielded by factions seeking no action to cut climate change risks, my description of him was not apt.

But the reaction from longtime contacts in environmental science was like a digital sledgehammer. An e-mail string excoriating the story was forwarded to me in hopes I would understand how far I had strayed. In the exchange, one of the country’s top sustainability scientists told the others: “I think I’m going to throw up. I kept trying to believe that Andy was quite good, albeit subject to occasional lapses as well as rightward pressure from NYT higher-ups. But this is really too much. We have all over-rated him.”

The intensity of feelings, the divergent views of data, prompted me to examine old questions in new ways. For twenty years, I’d been reporting on climate change as a mechanistic geophysical problem with biological implications and technical, economic, or regulatory solutions. As a science writer, I was so focused on the puzzle that, I suddenly realized, I had neglected to consider why so little was happening and why so many people found the issue boring or inconsequential.

Why is so little happening, after all? The science is indisputable. And, sure, yes, Congress and the mainstream news media are riddled with hacks. Most conservatives (Stephens included) resist energy reform policies that would get us started in the right direction, and, shit, the American electorate voted Donald Trump as president in 2016. Most liberals tend to resist energy reform, as well, insofar as it means actually consequentially changing how we interact with the planet. Marching for science is one thing; questioning the Grand Human Experiment as it stands is another.

But I didn’t see many people addressing those sorts of arguments. Rather, the discussion turned to the very thing that Revkin had warned us about last year: social media pressures and distractions, straw men, hyperbole. The discussion cemented Stephens’ column as a one-note chorus of climate change skepticism. “He is simply repeating falsehoods spread by various ‘think tanks’ funded by the fossil fuel industry,” Potsdam University climatologist Stefan Rahmstorf said.

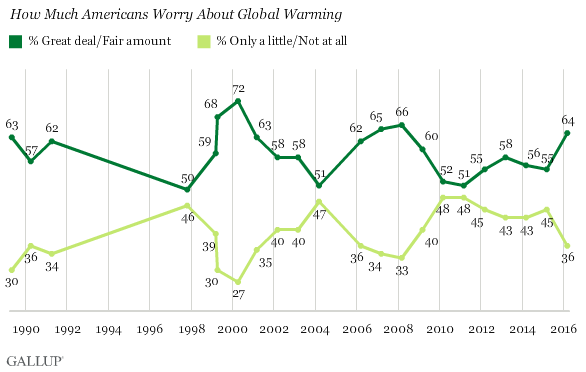

Wemple, at WashPo, joined many others in ripping specifically into New York Times editors. He pointed to this 2016 Gallup chart (see below) as “critical context for the movement on social media of people saying they’ve ended their subscriptions over the Stephens column.” But I’d suggest that the data only support Stephens’ column further. We’re at roughly the same exact level of global warming concern now than we were in 1990. And since then, the only discernible trend that I can see is that Americans grow less concerned with the Earth’s climate when there’s something more pressing — more headline-saturated — at play: 9/11 and the Iraq War and, later, the Great Recession. Climate change remains a fungible issue for a majority of Americans. (And that’s not even getting into the argument of whether caring a “great deal” or a “fair amount” actually equates to any active engagement with climate solutions.)

Wemple warned Stephens of “future clashes with social media,” which gets us closer to the real argument playing out in the wake of the column. The internet outrage machine is a powerful force, and it’s one of the few things that can survive through truly tragic and monumental events in the U.S. It is stronger than our concern for the planet, and it leads to media criticism being such a robust cottage industry these days.

Vox‘s David Roberts broke down the Stephens column in an exhaustively long rebuttal — and then an exhaustively long “tweetstorm” — contending mostly that “The column is an answer to this need: ‘the old way of fighting liberals on climate change isn’t working; I need to find new ways.'”

And that strikes at the central point here: It’s become vital to reduce major American problems (our influence on the climate, post-9/11 defense policy, economic reform and the bank bailout, etc.) as liberal-vs.-conservative dichotomies. You’re either on this side of the fence or that side of the fence, but both sides inherently condone the existence of the fence as the most important thing — not the original problem itself or the solution or even the arc of the debate.

These are major problems with the nature of humanity, really, and anyone denying that simple fact should immediately head toward the exits. My read of Stephens on this one is that he’s probing at how our global community is going to address the climate situation. I don’t see him advancing any noble solutions (the opposite, in fact, going nearly so far as to discourage policy reform) — and I see no use in bringing the First Amendment into this debate — but he raises important points that, on a long enough timeline, all communities need to address. While the Arctic ice shelf melts into oblivion, let’s stop frantically measuring everyone’s progressive/conservative dicks and actually, like, sit down and pragmatically strike at the root. (The climate problem touches many arenas of American life, including most prominently animal agriculture. Rarely, however, will you hear a climate change conversation get into the matter of dismantling the livestock industry. That would be something!)

Revkin again:

After dinner on the final evening [of a 2014 energy conference at the Vatican], in one of the ornate rooms of the Casina Pio IV, built as a summer home for Pope Pius IV in 1561, I turned to Walter Munk, the ninety-eight-year-old Scripps Institution oceanographer who, among other things, played a role in helping Allied amphibious invasions succeed by refining wave forecasts.

“What do you think it will take for humanity to have a smooth journey in this century?” I asked.

Munk didn’t mention science or technology, carbon capture or a carbon tax, fusion power or political will.

“This requires a miracle of love and unselfishness,” he said.

And there I was, a lifelong science writer in the Vatican, smiling and buoyed and chucking my stick-to-the-data “very serious person” persona and embracing the utterly human magic in that reply.

If the Stephens column serves any purpose, it’s to highlight the irrationality of an American constituency more concerned with being recognized for its concern of social ills than for actually doing much of anything about them. Like the snake that perpetually eats its own tail, the internet outrage machine will never be satisfied and will never truly go away. The machine does, however, gleefully, have one less subscription payment each month.